The Cinematic Orchestra

On Ninja Tune

BIOGRAPHY

It’s been twelve years since The Cinematic Orchestra released a studio album. At the time, in 2007, “Ma Fleur” was recognized for its bold departure from the group’s sonic traditions; in the years since, it’s been continuously celebrated, with tracks like ‘To Build A Home’ reaching huge audiences, spilling out of televisions, cinemas and radios long after its release.They didn’t disappear, the band have performed to larger and larger audiences and so...

It’s been twelve years since The Cinematic Orchestra released a studio album. At the time, in 2007, “Ma Fleur” was recognized for its bold departure from the group’s sonic traditions; in the years since, it’s been continuously celebrated, with tracks like ‘To Build A Home’ reaching huge audiences, spilling out of televisions, cinemas and radios long after its release.

They didn’t disappear, the band have performed to larger and larger audiences and sold out the likes of London's Royal Albert Hall, Philharmonie de Paris, Rome’s Auditorium Park Della and the Sydney Opera House. Coachella, Glastonbury, Fuji Rock, Montreux and Sonar have all played host to the band’s much loved live performances. They have also appeared at the Directors Guild Lifetime Achievement Awards for Stanley Kubrick and New York’s Summerstage with the legendary Mahavishnu Orchestra with John McLaughlin. They curated a series of events at London’s prestigious Barbican Centre featuring commissions from the prodigiously talented Austin Peralta (RIP) and seen the likes of Dorian Concept, Moses Sumney and Gilles Peterson support them on stage over the years.

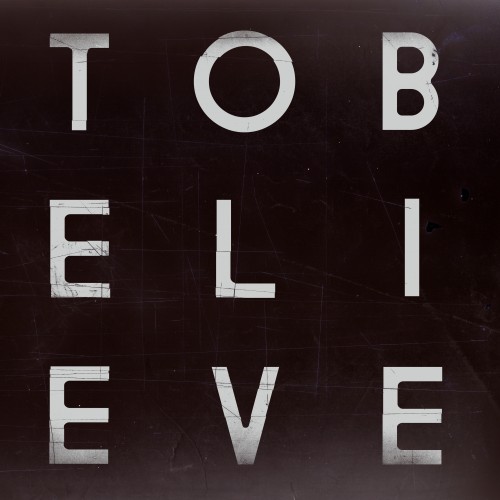

They’re back with a definitive new album that explores a timeless question of vital importance in 2019 - what to believe? The question of belief is one that has long simmered in the minds of Swinscoe and Smith. This album is a meditation on belief: an attempt to examine the shaky foundations which underpin it, while also emphasising its importance to our lives. “The prerequisite of everything in life is belief both good and bad” Smith says. “so what should we believe in...or what can we believe in and also importantly why do we believe in something".

Founding member Jason Swinscoe and longtime musical collaborator Dominic Smith enlisted album contributions from old and new: Moses Sumney, Roots Manuva, Heidi Vogel, Grey Reverend and Tawiah. Miguel Atwood-Ferguson features on strings, Dennis Hamm on keys and photographer and visual artist Brian “B+” Cross collaborated with Swinscoe and Smith on the album’s concept. The record was mixed by multiple Grammy winner Tom Elmhirst in Jimi Hendrix’s legendary Electric Lady studios. The album artwork comes courtesy of The Designers Republic. Guided by a communal spirit, the changing members are consistent with their ethos, where no individual ego takes precedence.

They announced the album with the release of new single ‘A Caged Bird / Imitations of Life’ featuring Roots Manuva. The track, revealed via an innovative website only accessible on offline devices - a paradox illuminating the album’s core question of what to believe - was available initially on 12" in independent record stores and sold out in a matter of hours. The artists first collaborated in 2002 on fan favourite ‘All Things to All Men’, and 17 years later the partnership has lost none of its urgency and searing insight, as Roots Manuva laments how our “situation is strange to us, stranger things are claiming us” over a pounding, hypnotic rhythm section that concedes to the choruses’ soaring strings.

In 2019 it is easy to see the band’s influence; jazz is all around us, London and LA have recently produced scenes more prolific than anyone expected; Kamasi Washington has been nominated for both Grammy and Brit Awards, Sons Of Kemet a Mercury Prize, BADBADNOTGOOD provide jazz soundtracks to high fashion shows and Kendrick Lamar has put the jazz palette at the top of the charts. When TCO released their critically acclaimed debut album Motion it helped pave the way for this moment, incorporating as it did a interpretation that had been lacking in the oeuvre and encouraging a new generation of musicians to break rules. ”’Motion’ came into a small international scene for this music which has grown and borne all sorts of fruit,” Smith says. “It pushed the narrative, people didn’t know they wanted until they were shown it, that’s what all great art is.” “To Believe” doesn’t shy away from this ethos - its articulation of the band’s unique sonic language, encompassing not only jazz but the sort of transcendental orchestration combined with the elegant electronics of artists like Ólafur Arnalds and Floating Points, artists they have helped forge a path for, has never been more cohesive and compelling.

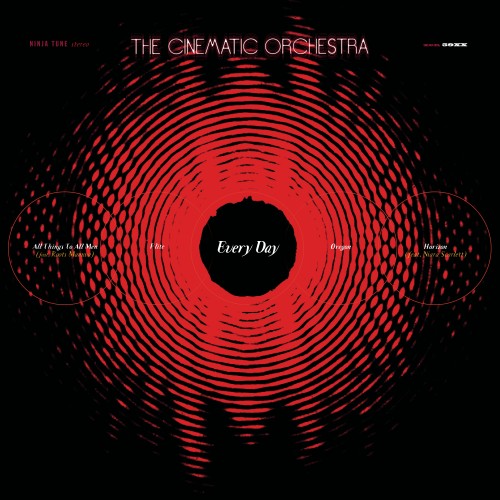

Since their 1999 debut, “Motion”, The Cinematic Orchestra have sold hundreds of thousands of albums, generated almost half a billion streams and enjoyed critical support from the likes of Pitchfork (8.6 for second album Every Day which featured two collaborations with legendary Art Ensemble of Chicago singer Fontella Bass), The Guardian, New York Times, Le Monde, Resident Advisor, Fader, Mixmag, NME, Crack (whose Simple Things festival the band headlined in 2016), Rolling Stone, Gilles Peterson, Benji B, Jason Bentley, Zane Lowe, Annie Mac, Lauren Laverne, KCRW and Mary Anne Hobbs. ‘To Build A Home’ has been synced to dozens of films and TV shows, including the Orange Is The New Black finale and This Is Us. Adverts include Burberry, Armani, Nike and Apple. The ‘To Build a Home’ short film was directed by Andrew Griffin and stars Peter Mullan (Trainspotting, Harry Potter).

On “To Believe”, Swinscoe and Smith continue to make music with an expansive vision, while also scaling up their ambition. recorded on a bigger scale geographically, with the record built from sessions in New York and London and LA, the latter being where the record first started to take shape, starting with a collaboration with Moses Sumney. Album closer ‘A Promise’, is a prime example of its broad connections, featuring longtime collaborator Heidi Vogel: assured and grandiose, accompanied by LA’s Miguel Atwood Ferguson’s mesmerising string arrangements; it’s a slow-burn release of the hopeful energy that’s pent up on the record. The track is delicate but explosive, precise but emotive; a perfect example of the different strands which are tied together through the record.

The record was made with narrative in mind with instrumental pauses from imagined movie scenes interjecting at just the right moments; something that they’ve honed through several scores composed for films. “Man With A Movie Camera”, released as an album in 2003, was the result of a commission in 2001, for the opening event for the Porto’s year as European City of Culture, where they were asked to write and perform a new score for Dziga Vertov’s avant garde 1929 silent film “Man With The Movie Camera”. And in 2008, Swinscoe wrote an original film score for Disney’s “The Crimson Wing”, an incredible, feature length nature documentary, which also closed out the end credits of the Oscar winning Stephen Hawking biopic, "Theory Of Everything”. The soundtrack picked up a nomination for ‘Best Original Score’ at Cannes, and film opened at the Empire Cinema in London’s Leicester Square.

A friend’s short story scripts were a vital guide to the completion of third studio album “Ma Fleur”, in 2007, which Swinscoe wrote following a move to Paris. Shortly after relocating, he began work on the instrumentals that would form the basis of the new record. Having completed a rough version by early 2005, he gave this to a friend, who disappeared for 3 weeks and came back with short story scripts in which each track represented a scene. Swinscoe then took this and worked some more on the tracks, and in turn gave this back to his scriptwriter, the two aspects of the project developing alongside one another. This yet-to-be-made movie gave Swinscoe the emotional and narrative impetus he needed to develop the pieces and, in particular, led him even further into his exploration of song than he had previously gone. “For me, I think it became a natural evolution to enquire into that whole new world of the song form,” he says. “Also I think the ‘screenplay’ experiment led to a need for a much more direct relationship to words and stories. So it still has links with film and narrative, in fact was driven by it.”

During this period, Smith had done his own fair share of travelling and musical experimentation. After working for years in Ninja Tune’s south London office, where he’d first met Swinsoe, he’d felt the magnetic pull of the as-yet-nameless experimental sound taking root in Los Angeles, and moved there full-time to take part in its blossoming. Ushered in largely by elder scene statesman Carlos Niño, he rubbed shoulders with all sorts of characters who’d soon weave themselves into the Cinematic fabric as naturally as everything seemed to happen out that way. The spirit of it all was persistently inclusive and open-minded; in contrast to the New York jazz scene, LA was eager to jam and to experiment, unafraid to get lost, and more often than not, fruitful in its finding.

In 2007, Swinscoe moved again, this time to Brooklyn, with a tremendous optimism suited to the new landscape. Coming to America meant immersing himself in an entirely new scene and drawing nearer to influences that had informed his collecting and creating from day one. “I think the cities I’ve lived in have had an effect on my perspective both personally and musically,” he says. “The dynamics of a city change the energy and pace of all things, but particularly music.”

Swinscoe took to exploring the neighborhood, and his hanging around a local coffee shop turned serendipitous when he was moved by music playing overhead one day. He asked for an ID from one of the staff members, who with some shyness claimed it as his own. Larry Brown – former barista at that coffee shop, vocalist and musician who also goes by the name Grey Reverend – became a fast friend. Swinscoe had found a creative partner who was kindred in taste. Between them, the extended web of contributors, and the genesis of Swinscoe’s new life in New York, ideas were aplenty.

Swinscoe and Smith later reconnected with Brown in the making of “To Believe”, the latter’s vocals as Grey Reverend taking centre stage on track ‘Zero One / This Fantasy’, a song which circles around the record’s key theme of belief. In this case, it nods to the ideas of the academic Anil Seth, whose ideas about reality – specifically, how everyone’s idea of it is socially constructed – was a big influence on Smith and Swinscoe. As Reverend’s lyrics muse, “In this fantasy / Everyone is someone to believe,” hinting at the slanted viewpoint through which each of us sees the world.

But before these forward steps had been made, Swinscoe spent his time in Brooklyn faced with too many options. Too much of anything – cash, booze, praise, time, voices eager to help – creates noise without isolating any one sound’s resonance. More studio toys had been acquired, more minds added to the band’s songwriting hive, more confidence in exploring the unfamiliar, and with it more potential paths to tread. Time pressed on. Trying, trying, trying. Five years, and not one bulb flashed in Swinscoe’s swinging through the dark. Then Dominic Smith made a centuries-old suggestion: where better to rediscover brightness than further into the American west?

So off in search they went. But before the journey, there was a return: Swinscoe landed in his LA bungalow and unboxed only his sampler, a throwback to his earliest days of composing on a Korg with so little memory that each saved sample necessitated perfection. Simplifying and re-connecting to both a process and a kinship that came naturally to them was an energetic turning point, and one by one others were to come into the fold, always out of some destined happenstance, seemingly magnetized too.

As the band’s musical web spun itself back into form, Swinscoe and Smith also began to explore different means of articulation; they’d always buried messages in metaphorical lyrics and artwork, but something made their delivery now feel more important, more urgent. Both longed for the time when music felt inherently and inescapably political, yet as the album began to come together it felt as though no one was sounding out a rally cry – this was still pre-Brexit, pre-Trump, before music began to find its voice of resistance again, if only out of necessity.

Luke Flowers, a constant throughout The Cinematic Orchestra discography, was woven into this musical process early on. As ever, the drummer’s adept skills behind the drum kit were called upon to give the record the restrained-yet-powerful rhythmic backbone. On ‘Lessons’, for instance, the melodic, melancholy meditation is built around Flowers’ constant playing, driving the track’s ebbs and flows of energy. An under-the-radar drumming hero, Flowers is an integral part of the group’s sound.

Around this time, they found themselves in the same Japanese diner as Smith’s longtime friend Brian “B+” Cross. B+ had documented and participated in the city’s sample-based sonic diaspora for years as part of visual production outfit MOCHILLA, but wasn’t exactly an obvious band-member to anyone’s eye. Yet catching up over eggs they realized a common interest in arthouse film theory and visual phenomena, and B+ fell seamlessly into the mix as a kind of conceptual consultant as the project developed. His encyclopedic knowledge of perceptual trickery and illusion connected both to the band’s cinematic pedigree and their restless desire for music with meaning. B+’s contributions are not that of a documentarian peering into the band’s world but rather a set of eyes, unblinking, on the inside.

B+’s influence was not just theoretical either. Through his film work with MOCHILLA he’d recorded an arresting and acrobatic one-take rendition of what would go on to be Moses Sumney’s first breakout song, ‘Replaceable’. Traditionally The Cinematic Orchestra’s roster of vocalists has been malleable and hand-picked according to each track’s sound, in a sense casted for their leading role in the micro-odyssey of a particular project. After B+ shared the video with the band, they tapped Moses for what became “To Believe”’s willowy title track, first released as a single in 2016. In a way the collaboration is symbolic of the band’s entire legacy–Sumney’s allegorical songwriting and zeitgeisty talent sits snugly alongside predecessors like Fontella Bass and Patrick Watson, while his connection to the prosperous pool of talent in LA captures the band’s gaze toward the future.

Next came Miguel Atwood-Ferguson, a figure deeply woven into the Los Angeles musical fabric and an astute addition to the TCO sound. Historically, most of the band’s strings had been arranged “in-house,” rooted in the bank of old film scores, American jazz and funk that both Smith and Swinscoe collected and drew from voraciously. Atwood-Ferguson’s sensibilities as a composer – his sections often in the background, sweeping through the harmonic ether dramatically yet with restraint – were a dynamic accompaniment to many figures in LA circuit at the time, and fit seamlessly alongside those of the Orchestra. His strings recordings across all the tracks on the new record, in collaboration with Swinscoe and Smith, simultaneously give them more float and gravity than ever.

Los Angeles proved to be fertile ground not only for local talent but reconnecting with faraway friends too. For one, Oliver Johnson, also known as Dorian Concept, had been orbiting similar suns for years – he’d developed a career as a keyboardist and producer in his own right while lending playing and production to others in the Brainfeeder cosmos. His sensitivity to texture and melody was something he credited in part to a “studentship” of The Cinematic Orchestra’s early output, obsessively playing “Motion” with high school friends and studying its credits to render his own vision of uncompromising, contemporary jazz. As writing on the record neared its end, Johnson was called upon to add colour to some of its shadowy moments, even the quietude turned effervescent.

This wasn’t the first time Johnson had worked with the band. Around the time of “Motion”, he’d gotten in touch with Tom Chant – the free saxophonist who had worked most directly with Swinscoe in the first record’s making – and later collaborated with him to re-imagine the score to a film by Austrian director Peter Tscherkassky as part of TCO’s In:Motion project. Chant in many ways embodies the evolving symbiosis of the band: a friend-of-a-friend turned studio partner turned bedrock of the band’s live formation over two decades. Though the band’s activity has had its ebbs and flows, the scope of its organic dynamism has only matured. And while the heart of the record beats in LA, it still counts other voices in its harmony and other geographies

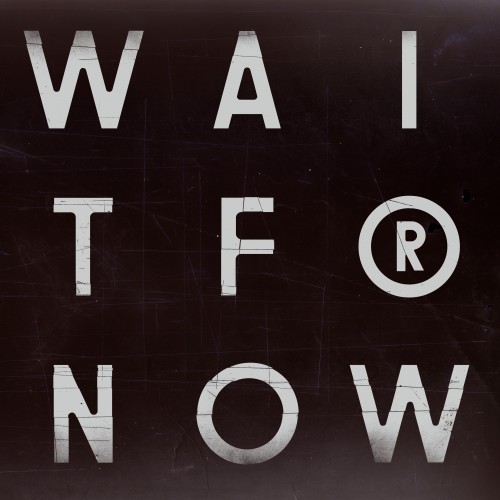

‘Wait For Now / Leave The World’ is a prime example. Featuring soul singer Tawiah (Mark Ronson band), based in the UK, she’s another artist who’s entered the group’s welcoming orbit before. Her lyrics celebrate the possibilities which can come from moving and leaving your comfort zone. In the track’s opening lines, she sings, “Take my hand and see / Where we could go, when you take the leap.” Fittingly, it’s also one of the entries benefiting from Johnson’s masterful keys work, adding extra texture to the track’s twinkling effervescence, and underscoring the far-flung connections which sit as the album’s foundation.

In this sense, the band’s recorded absence is less a break than an embrace of its unique relationship with space, with kinship, with dissent, of course with art and sound, but most of all, with one another.

The Cinematic Orchestra

On Ninja Tune

Albums

Singles

Latest News

BIOGRAPHY

It’s been twelve years since The Cinematic Orchestra released a studio album. At the time, in 2007, “Ma Fleur” was recognized for its bold departure from the group’s sonic traditions; in the years since, it’s been continuously celebrated, with tracks like ‘To Build A Home’ reaching huge audiences, spilling out of televisions, cinemas and radios long after its release.They didn’t disappear, the band have performed to larger and larger audiences and sold out the likes of ...

It’s been twelve years since The Cinematic Orchestra released a studio album. At the time, in 2007, “Ma Fleur” was recognized for its bold departure from the group’s sonic traditions; in the years since, it’s been continuously celebrated, with tracks like ‘To Build A Home’ reaching huge audiences, spilling out of televisions, cinemas and radios long after its release.

They didn’t disappear, the band have performed to larger and larger audiences and sold out the likes of London's Royal Albert Hall, Philharmonie de Paris, Rome’s Auditorium Park Della and the Sydney Opera House. Coachella, Glastonbury, Fuji Rock, Montreux and Sonar have all played host to the band’s much loved live performances. They have also appeared at the Directors Guild Lifetime Achievement Awards for Stanley Kubrick and New York’s Summerstage with the legendary Mahavishnu Orchestra with John McLaughlin. They curated a series of events at London’s prestigious Barbican Centre featuring commissions from the prodigiously talented Austin Peralta (RIP) and seen the likes of Dorian Concept, Moses Sumney and Gilles Peterson support them on stage over the years.

They’re back with a definitive new album that explores a timeless question of vital importance in 2019 - what to believe? The question of belief is one that has long simmered in the minds of Swinscoe and Smith. This album is a meditation on belief: an attempt to examine the shaky foundations which underpin it, while also emphasising its importance to our lives. “The prerequisite of everything in life is belief both good and bad” Smith says. “so what should we believe in...or what can we believe in and also importantly why do we believe in something".

Founding member Jason Swinscoe and longtime musical collaborator Dominic Smith enlisted album contributions from old and new: Moses Sumney, Roots Manuva, Heidi Vogel, Grey Reverend and Tawiah. Miguel Atwood-Ferguson features on strings, Dennis Hamm on keys and photographer and visual artist Brian “B+” Cross collaborated with Swinscoe and Smith on the album’s concept. The record was mixed by multiple Grammy winner Tom Elmhirst in Jimi Hendrix’s legendary Electric Lady studios. The album artwork comes courtesy of The Designers Republic. Guided by a communal spirit, the changing members are consistent with their ethos, where no individual ego takes precedence.

They announced the album with the release of new single ‘A Caged Bird / Imitations of Life’ featuring Roots Manuva. The track, revealed via an innovative website only accessible on offline devices - a paradox illuminating the album’s core question of what to believe - was available initially on 12" in independent record stores and sold out in a matter of hours. The artists first collaborated in 2002 on fan favourite ‘All Things to All Men’, and 17 years later the partnership has lost none of its urgency and searing insight, as Roots Manuva laments how our “situation is strange to us, stranger things are claiming us” over a pounding, hypnotic rhythm section that concedes to the choruses’ soaring strings.

In 2019 it is easy to see the band’s influence; jazz is all around us, London and LA have recently produced scenes more prolific than anyone expected; Kamasi Washington has been nominated for both Grammy and Brit Awards, Sons Of Kemet a Mercury Prize, BADBADNOTGOOD provide jazz soundtracks to high fashion shows and Kendrick Lamar has put the jazz palette at the top of the charts. When TCO released their critically acclaimed debut album Motion it helped pave the way for this moment, incorporating as it did a interpretation that had been lacking in the oeuvre and encouraging a new generation of musicians to break rules. ”’Motion’ came into a small international scene for this music which has grown and borne all sorts of fruit,” Smith says. “It pushed the narrative, people didn’t know they wanted until they were shown it, that’s what all great art is.” “To Believe” doesn’t shy away from this ethos - its articulation of the band’s unique sonic language, encompassing not only jazz but the sort of transcendental orchestration combined with the elegant electronics of artists like Ólafur Arnalds and Floating Points, artists they have helped forge a path for, has never been more cohesive and compelling.

Since their 1999 debut, “Motion”, The Cinematic Orchestra have sold hundreds of thousands of albums, generated almost half a billion streams and enjoyed critical support from the likes of Pitchfork (8.6 for second album Every Day which featured two collaborations with legendary Art Ensemble of Chicago singer Fontella Bass), The Guardian, New York Times, Le Monde, Resident Advisor, Fader, Mixmag, NME, Crack (whose Simple Things festival the band headlined in 2016), Rolling Stone, Gilles Peterson, Benji B, Jason Bentley, Zane Lowe, Annie Mac, Lauren Laverne, KCRW and Mary Anne Hobbs. ‘To Build A Home’ has been synced to dozens of films and TV shows, including the Orange Is The New Black finale and This Is Us. Adverts include Burberry, Armani, Nike and Apple. The ‘To Build a Home’ short film was directed by Andrew Griffin and stars Peter Mullan (Trainspotting, Harry Potter).

On “To Believe”, Swinscoe and Smith continue to make music with an expansive vision, while also scaling up their ambition. recorded on a bigger scale geographically, with the record built from sessions in New York and London and LA, the latter being where the record first started to take shape, starting with a collaboration with Moses Sumney. Album closer ‘A Promise’, is a prime example of its broad connections, featuring longtime collaborator Heidi Vogel: assured and grandiose, accompanied by LA’s Miguel Atwood Ferguson’s mesmerising string arrangements; it’s a slow-burn release of the hopeful energy that’s pent up on the record. The track is delicate but explosive, precise but emotive; a perfect example of the different strands which are tied together through the record.

The record was made with narrative in mind with instrumental pauses from imagined movie scenes interjecting at just the right moments; something that they’ve honed through several scores composed for films. “Man With A Movie Camera”, released as an album in 2003, was the result of a commission in 2001, for the opening event for the Porto’s year as European City of Culture, where they were asked to write and perform a new score for Dziga Vertov’s avant garde 1929 silent film “Man With The Movie Camera”. And in 2008, Swinscoe wrote an original film score for Disney’s “The Crimson Wing”, an incredible, feature length nature documentary, which also closed out the end credits of the Oscar winning Stephen Hawking biopic, "Theory Of Everything”. The soundtrack picked up a nomination for ‘Best Original Score’ at Cannes, and film opened at the Empire Cinema in London’s Leicester Square.

A friend’s short story scripts were a vital guide to the completion of third studio album “Ma Fleur”, in 2007, which Swinscoe wrote following a move to Paris. Shortly after relocating, he began work on the instrumentals that would form the basis of the new record. Having completed a rough version by early 2005, he gave this to a friend, who disappeared for 3 weeks and came back with short story scripts in which each track represented a scene. Swinscoe then took this and worked some more on the tracks, and in turn gave this back to his scriptwriter, the two aspects of the project developing alongside one another. This yet-to-be-made movie gave Swinscoe the emotional and narrative impetus he needed to develop the pieces and, in particular, led him even further into his exploration of song than he had previously gone. “For me, I think it became a natural evolution to enquire into that whole new world of the song form,” he says. “Also I think the ‘screenplay’ experiment led to a need for a much more direct relationship to words and stories. So it still has links with film and narrative, in fact was driven by it.”

During this period, Smith had done his own fair share of travelling and musical experimentation. After working for years in Ninja Tune’s south London office, where he’d first met Swinsoe, he’d felt the magnetic pull of the as-yet-nameless experimental sound taking root in Los Angeles, and moved there full-time to take part in its blossoming. Ushered in largely by elder scene statesman Carlos Niño, he rubbed shoulders with all sorts of characters who’d soon weave themselves into the Cinematic fabric as naturally as everything seemed to happen out that way. The spirit of it all was persistently inclusive and open-minded; in contrast to the New York jazz scene, LA was eager to jam and to experiment, unafraid to get lost, and more often than not, fruitful in its finding.

In 2007, Swinscoe moved again, this time to Brooklyn, with a tremendous optimism suited to the new landscape. Coming to America meant immersing himself in an entirely new scene and drawing nearer to influences that had informed his collecting and creating from day one. “I think the cities I’ve lived in have had an effect on my perspective both personally and musically,” he says. “The dynamics of a city change the energy and pace of all things, but particularly music.”

Swinscoe took to exploring the neighborhood, and his hanging around a local coffee shop turned serendipitous when he was moved by music playing overhead one day. He asked for an ID from one of the staff members, who with some shyness claimed it as his own. Larry Brown – former barista at that coffee shop, vocalist and musician who also goes by the name Grey Reverend – became a fast friend. Swinscoe had found a creative partner who was kindred in taste. Between them, the extended web of contributors, and the genesis of Swinscoe’s new life in New York, ideas were aplenty.

Swinscoe and Smith later reconnected with Brown in the making of “To Believe”, the latter’s vocals as Grey Reverend taking centre stage on track ‘Zero One / This Fantasy’, a song which circles around the record’s key theme of belief. In this case, it nods to the ideas of the academic Anil Seth, whose ideas about reality – specifically, how everyone’s idea of it is socially constructed – was a big influence on Smith and Swinscoe. As Reverend’s lyrics muse, “In this fantasy / Everyone is someone to believe,” hinting at the slanted viewpoint through which each of us sees the world.

But before these forward steps had been made, Swinscoe spent his time in Brooklyn faced with too many options. Too much of anything – cash, booze, praise, time, voices eager to help – creates noise without isolating any one sound’s resonance. More studio toys had been acquired, more minds added to the band’s songwriting hive, more confidence in exploring the unfamiliar, and with it more potential paths to tread. Time pressed on. Trying, trying, trying. Five years, and not one bulb flashed in Swinscoe’s swinging through the dark. Then Dominic Smith made a centuries-old suggestion: where better to rediscover brightness than further into the American west?

So off in search they went. But before the journey, there was a return: Swinscoe landed in his LA bungalow and unboxed only his sampler, a throwback to his earliest days of composing on a Korg with so little memory that each saved sample necessitated perfection. Simplifying and re-connecting to both a process and a kinship that came naturally to them was an energetic turning point, and one by one others were to come into the fold, always out of some destined happenstance, seemingly magnetized too.

As the band’s musical web spun itself back into form, Swinscoe and Smith also began to explore different means of articulation; they’d always buried messages in metaphorical lyrics and artwork, but something made their delivery now feel more important, more urgent. Both longed for the time when music felt inherently and inescapably political, yet as the album began to come together it felt as though no one was sounding out a rally cry – this was still pre-Brexit, pre-Trump, before music began to find its voice of resistance again, if only out of necessity.

Luke Flowers, a constant throughout The Cinematic Orchestra discography, was woven into this musical process early on. As ever, the drummer’s adept skills behind the drum kit were called upon to give the record the restrained-yet-powerful rhythmic backbone. On ‘Lessons’, for instance, the melodic, melancholy meditation is built around Flowers’ constant playing, driving the track’s ebbs and flows of energy. An under-the-radar drumming hero, Flowers is an integral part of the group’s sound.

Around this time, they found themselves in the same Japanese diner as Smith’s longtime friend Brian “B+” Cross. B+ had documented and participated in the city’s sample-based sonic diaspora for years as part of visual production outfit MOCHILLA, but wasn’t exactly an obvious band-member to anyone’s eye. Yet catching up over eggs they realized a common interest in arthouse film theory and visual phenomena, and B+ fell seamlessly into the mix as a kind of conceptual consultant as the project developed. His encyclopedic knowledge of perceptual trickery and illusion connected both to the band’s cinematic pedigree and their restless desire for music with meaning. B+’s contributions are not that of a documentarian peering into the band’s world but rather a set of eyes, unblinking, on the inside.

B+’s influence was not just theoretical either. Through his film work with MOCHILLA he’d recorded an arresting and acrobatic one-take rendition of what would go on to be Moses Sumney’s first breakout song, ‘Replaceable’. Traditionally The Cinematic Orchestra’s roster of vocalists has been malleable and hand-picked according to each track’s sound, in a sense casted for their leading role in the micro-odyssey of a particular project. After B+ shared the video with the band, they tapped Moses for what became “To Believe”’s willowy title track, first released as a single in 2016. In a way the collaboration is symbolic of the band’s entire legacy–Sumney’s allegorical songwriting and zeitgeisty talent sits snugly alongside predecessors like Fontella Bass and Patrick Watson, while his connection to the prosperous pool of talent in LA captures the band’s gaze toward the future.

Next came Miguel Atwood-Ferguson, a figure deeply woven into the Los Angeles musical fabric and an astute addition to the TCO sound. Historically, most of the band’s strings had been arranged “in-house,” rooted in the bank of old film scores, American jazz and funk that both Smith and Swinscoe collected and drew from voraciously. Atwood-Ferguson’s sensibilities as a composer – his sections often in the background, sweeping through the harmonic ether dramatically yet with restraint – were a dynamic accompaniment to many figures in LA circuit at the time, and fit seamlessly alongside those of the Orchestra. His strings recordings across all the tracks on the new record, in collaboration with Swinscoe and Smith, simultaneously give them more float and gravity than ever.

Los Angeles proved to be fertile ground not only for local talent but reconnecting with faraway friends too. For one, Oliver Johnson, also known as Dorian Concept, had been orbiting similar suns for years – he’d developed a career as a keyboardist and producer in his own right while lending playing and production to others in the Brainfeeder cosmos. His sensitivity to texture and melody was something he credited in part to a “studentship” of The Cinematic Orchestra’s early output, obsessively playing “Motion” with high school friends and studying its credits to render his own vision of uncompromising, contemporary jazz. As writing on the record neared its end, Johnson was called upon to add colour to some of its shadowy moments, even the quietude turned effervescent.

This wasn’t the first time Johnson had worked with the band. Around the time of “Motion”, he’d gotten in touch with Tom Chant – the free saxophonist who had worked most directly with Swinscoe in the first record’s making – and later collaborated with him to re-imagine the score to a film by Austrian director Peter Tscherkassky as part of TCO’s In:Motion project. Chant in many ways embodies the evolving symbiosis of the band: a friend-of-a-friend turned studio partner turned bedrock of the band’s live formation over two decades. Though the band’s activity has had its ebbs and flows, the scope of its organic dynamism has only matured. And while the heart of the record beats in LA, it still counts other voices in its harmony and other geographies

‘Wait For Now / Leave The World’ is a prime example. Featuring soul singer Tawiah (Mark Ronson band), based in the UK, she’s another artist who’s entered the group’s welcoming orbit before. Her lyrics celebrate the possibilities which can come from moving and leaving your comfort zone. In the track’s opening lines, she sings, “Take my hand and see / Where we could go, when you take the leap.” Fittingly, it’s also one of the entries benefiting from Johnson’s masterful keys work, adding extra texture to the track’s twinkling effervescence, and underscoring the far-flung connections which sit as the album’s foundation.

In this sense, the band’s recorded absence is less a break than an embrace of its unique relationship with space, with kinship, with dissent, of course with art and sound, but most of all, with one another.